He was born during the middle years of America’s Second Great Awakening. It was a time when exhorters walked the land. Exhorters preached. Exhorters prayed in public. Exhorters held meetings. Exhorters established churches, often beginning with a small group of believers coming together in a humble home.

Some exhorters were self-appointed. Some were incompetent. Some were grifters. Some were instruments in the accomplishment of great things. Organized denominations, like the Methodists and United Brethren in Christ, vetted and licensed exhorters before authorizing them to evangelize. It was evident to Methodist and United Brethren bishops that exhorters were necessary to fulfil Christ’s Great Commision to spread the gospel when the denominations themselves did not have enough ordained clergy in the field. The spiritual harvest demanded workers.

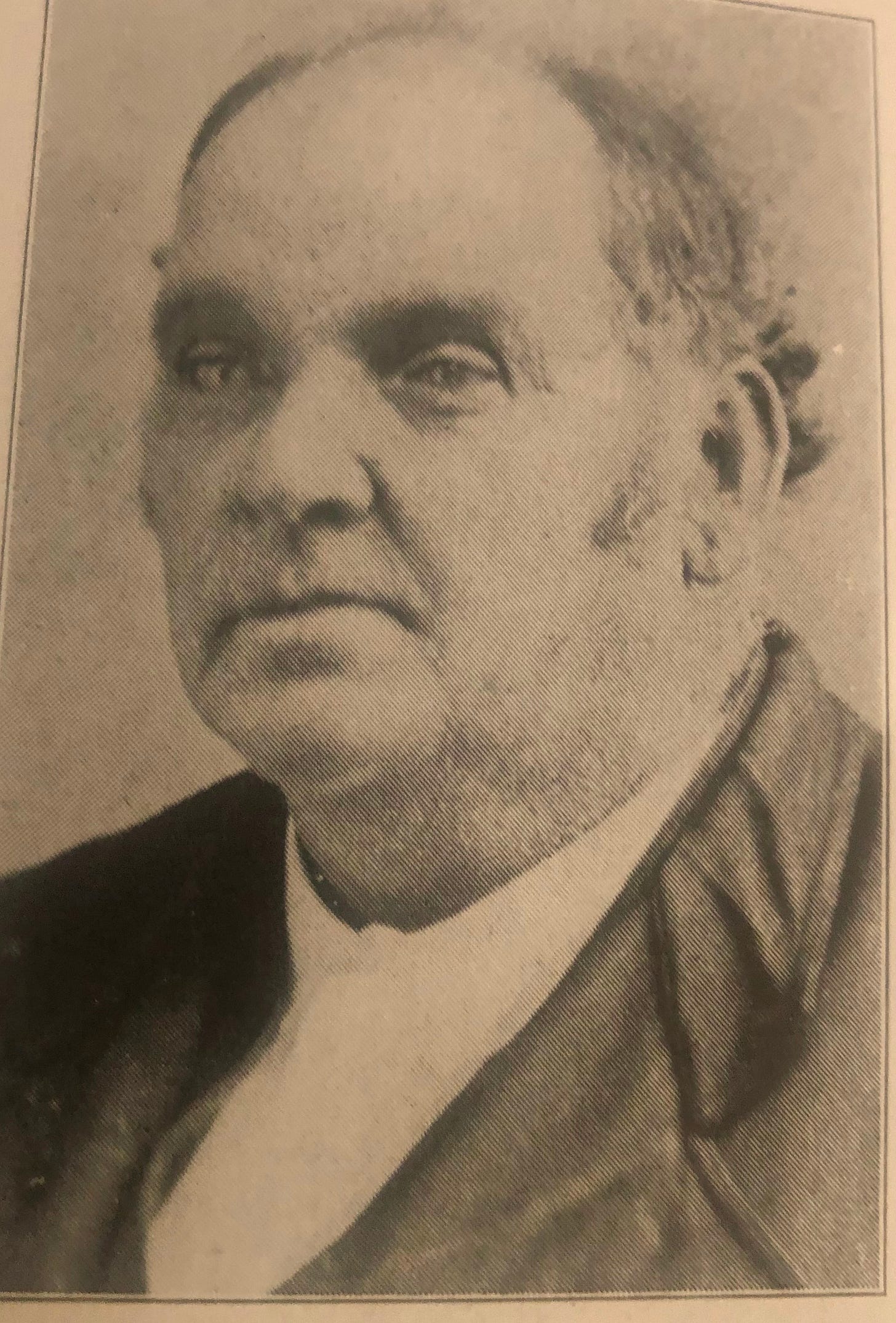

I don’t know if William Cadman was ever an exhorter. Or what his experience as a youth might have been with them. It is recorded that as a boy he went west from somewhere along French Creek in Erie County, Pennsylvania, in a “prairie schooner” with his parents to Iowa, and that, not much more than a boy, he was a soldier in the Mexican War. It is recorded specifically that on October 17, 1851, at age 23, he was, in central Ohio, received into the United Brethren. A year later he married Permelia Houck of Berlin, Ohio. A year after that he was ordained into the United Brethren ministry.

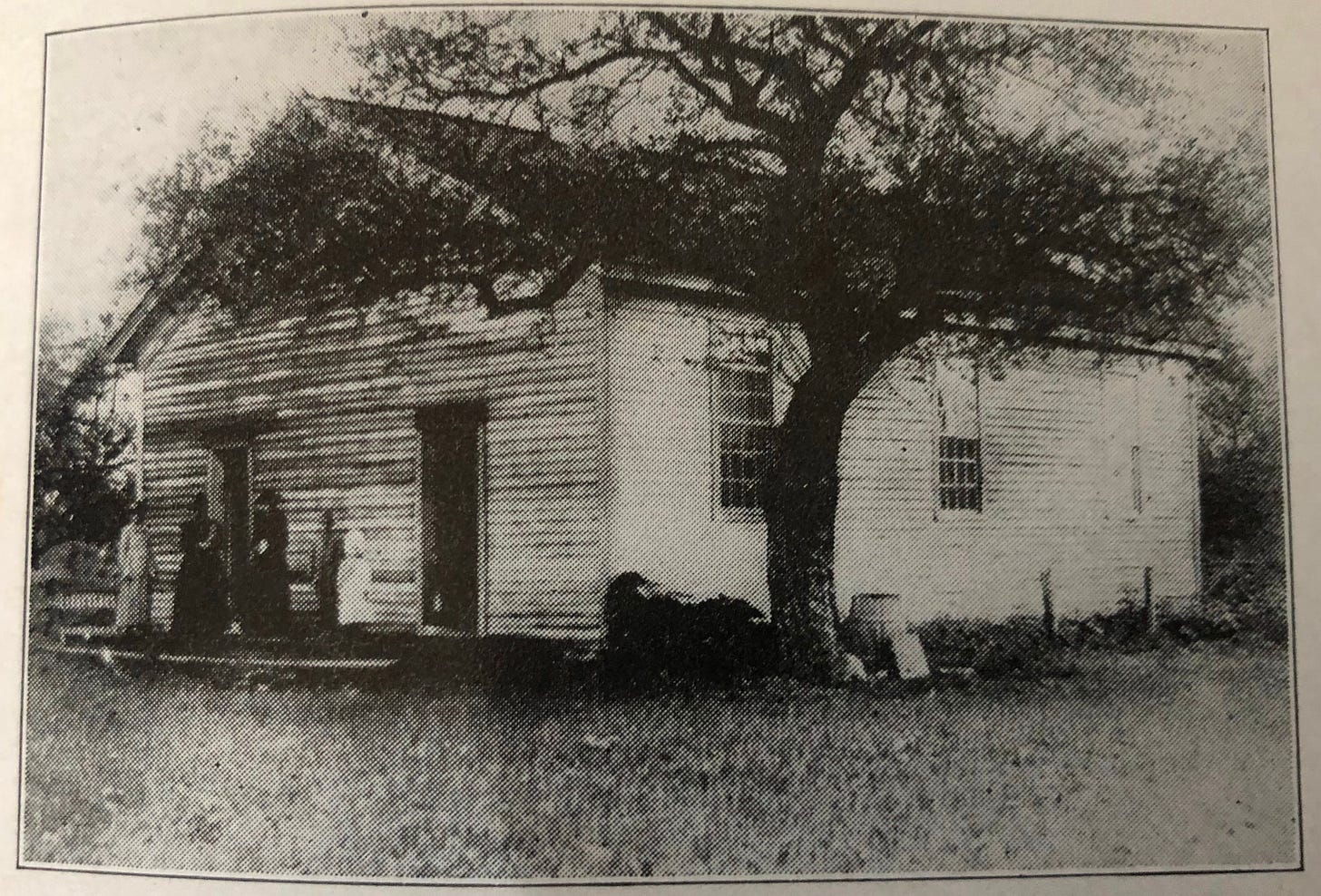

Not long after his ordination, he was sent, with a select group of United Brethren clergy and exhorters from central Ohio, to save the lost and organize churches in northwestern Pennsylvania. William and Permelia were apparently serious about their commitment — to Christ and to each other. They purchased a home on Stilson Hill near Sugar Grove, Pennsylvania. Their first daughter, Emma, was born there the year of their arrival.

The intentionality of the United Brethren in selecting Sugar Grove, in 1853, as the locus from which to begin their mission is, to me anyway, interesting. Founded in 1797, the name was derived from the surrounding maple forest. The village and surrounding area had been settled by sturdy pioneers from New England. Sugar Grove and its environs from a historical perspective might seem hardly to be differentiated from many other villages and surrounding areas settled within the scope of the Great New England Migration westward.

Except that Sugar Grove was a station in the Underground Railroad. And, in the summer of 1854, the place hosted on one of its farms a notable convention of abolitionists which featured an address, among others, by Frederick Douglass. I can only wonder if William and Permelia were witnesses to the former slaves speaking on the hillside of the doughty Scotsman James Younie’s farm during the late afternoon or early evening of the Saturday and Sunday just before the summer solstice.

The United Brethren mission to northwest Pennsylvania bore fruit, and within a few years the denomination gave it an official designation — the “Erie Conference.” In his early thirties, coinciding with the Civil War, Reverend Cadman was raised to the status of presiding elder — which meant he organized and supervised individual churches within his charge, sometimes filled in as a pastor for a particular church, and served as an evangelist within the conference. Cadman’s charge also meant he spent a great deal of time away from Permelia and Stilson Hill — for his charge reached to Harbor Creek along the Lake Erie shore some forty miles from Sugar Grove and to churches along the French and Oil Creeks well to the west of Sugar Grove.

Cadman was a big man — about 300 pounds. He had a loud voice and a charismatic personality. A bishop of his church remembered him as a “pent-up soul” who “preached as though he actually believed all he said.”

That same bishop said that Cadman’s “very earnestness alone seemed like a drawing power that was almost irresistible. One of his choice themes was ‘the Fatherhood of God,’ and ‘the universal brotherhood of man.’ He really seemed to weave a thread of this sentiment into nearly every sermon he preached. This is how he made me believe that I was his brother. I believe it still.”

An associate (at that time an exhorter, later a reverend) of Cadman in the early days of their ministry in northwest Pennsylvania said, “he was a very ‘son of thunder,’ being physically strong and magnetic. He possessed a voice and bearing of one born to command, and the people felt they must obey. At times he was extravagant in his hyperbole but never failed to charm and interest his hearers. At the many camp meetings he attended, he was always the leading spirit, and the attendants never wanted to miss the services conducted by him.”

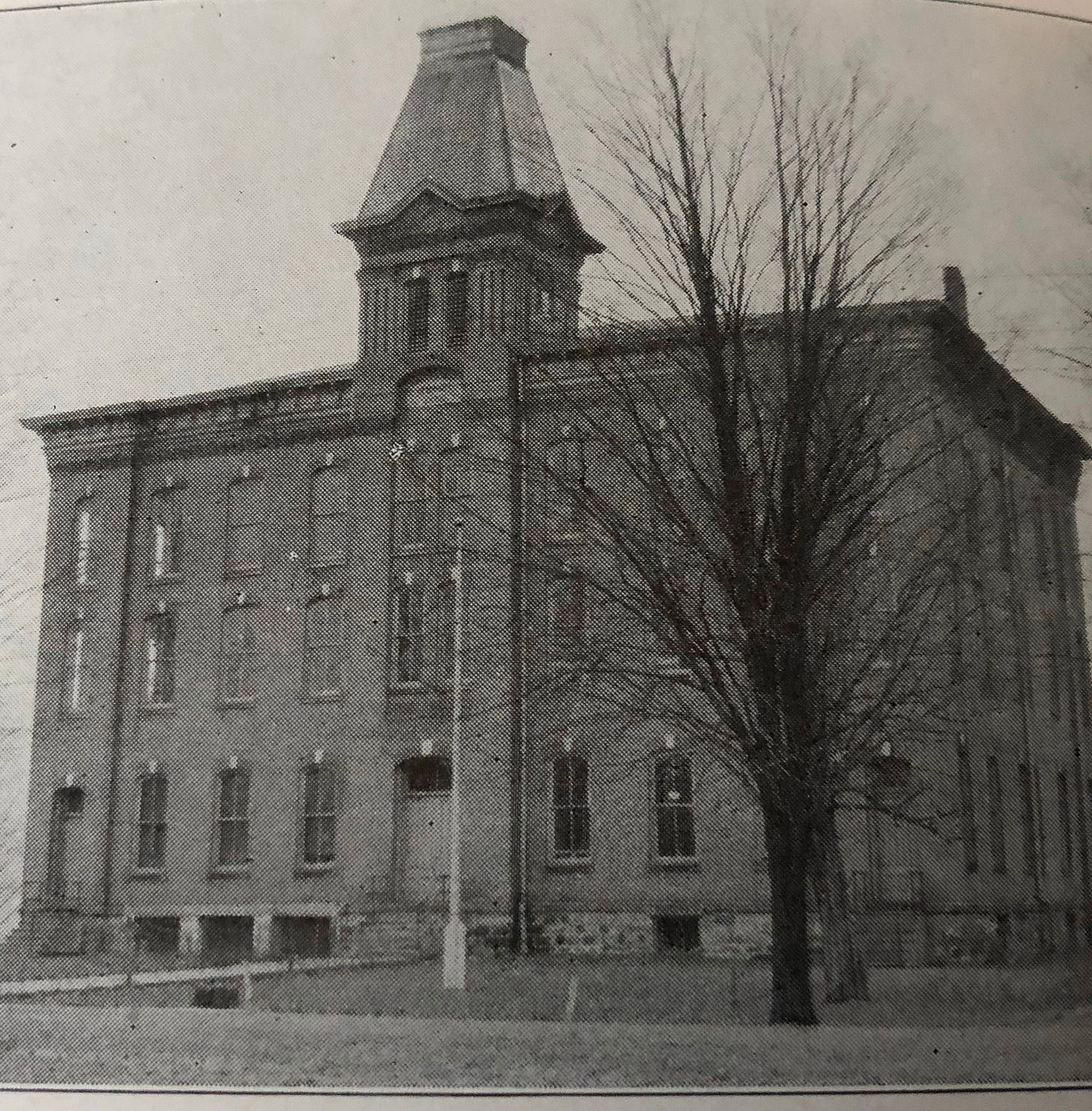

An actual academic (in contrast to the informally educated Cadman) who for fourteen years oversaw the United Brethren Seminary and Conservatory built in Sugar Grove in 1884 remembered that Cadman “was a very gifted man. His voice was one of rare power and sweetness. His enthusiasm and courage were contagious, so people flocked to hear him. There never was a man in Erie Conference who attracted such large audiences. One always wanted to know what he was going to say next. His faith was simple and strong. There was an extravagance about his speech and illustrations that amused and impressed his hearers.”

His hearers could also wonder what he might do next. One evening during a service at which Cadman was preaching, a listener under the influence of alcohol got up and demanded to see a miracle. Cadman tried to quiet him but to no effect. Then Cadman left the pulpit to confront the heckler directly. “We don’t perform miracles, but we do cast out devils!” he announced, and thereupon physically removed the man from the premises.

On another occasion two men under the influence feigned to respond to an altar call and at the altar disruptively proceeded to pray aloud. Cadman knelt between the two men and placed his powerful arms around them until the men began to squirm. Under the pressure and the slapping of their backs, the men began to repent of their behavior. According to the story, both were converted. In the annual report to the conference of the salvific results of his ministry for that year, Cadman included these two men into whom he had “pounded religion.”

Cadman served throughout the Erie Conference as a presiding elder for 30 years. At age 62, he retired to Permelia and their farm on Stilson Hill where they, or she mostly, had raised their five daughters. William and Permelia would live on their farm together for another ten years, though in no small measure of those years William was afflicted with illness “of long duration.”

On December 22, 1899, the famous evangelist Dwight Moody died at his farm in Northfield, Massachusetts. Three weeks later, on January 11, 1900, another great evangelist, died at his. Isaac Bennehoff, whom Cadman had mentored into the ministry during the early years in northwest Pennsylvania, attended him during his last hours. According to Bennehoff, Cadman’s last words were, “Beautiful! Beautiful! How beautiful beyond the stream!”

Permelia survived her husband by four years almost to the day. As she died it was recorded that he waved her hand and said, “There is a light on other shore.” William and Permelia are buried in a cemetery on Stilson Hill Road.

Thank you for reading In Penn’s Woods. I hope you have a wonderful and blessed holiday season. I am going to lay my Substack cudgel aside for a while, intending to take it up again sometime in the New Year. — Mike

Sources and Notes:

S. Paul Weaver. History of the Erie Conference of the Church of the United Brethren in Christ. Published by the UB Erie Conference, 1936. The historical photographs are culled from this book.

J.S. Shenck. History of Warren County, Pennsylvania. 1887. pp 420-442.

The Sugar Grove Seminary and Conservatory was more college preparatory than college. It was built when high schools were rare in the United States. Though under the auspices of the United Brethren in Christ, the citizens of Sugar Grove also contributed to its founding and thus its doors were open in a non-sectarian manner — though the denomination benefited in the enhanced quality of the persons who had their rough edges removed at the seminary and conservatory and who went into ministry in the Erie Conference. When Sugar Grove wanted a high school of its own, the seminary was closed, the structure razed, and a public school built on the site. The bell once atop the seminary can still be seen in front of Sugar Grove’s elementary school.