The Tariff in Their Times -- and Ours

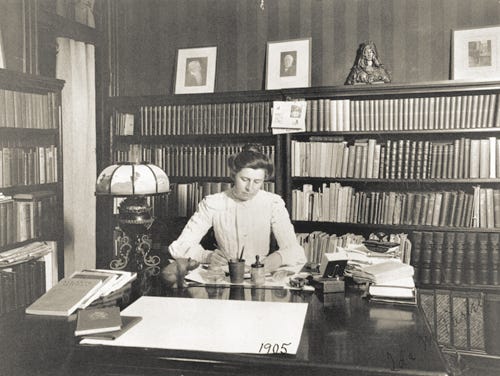

An explainer, beginning with Ida M. Tarbell.

Ida M. Tarbell’s reputation endures even as her work nowadays is seldom read. She was born some dozen miles from where I live. But my local public library maintains only one of her books in its stacks.

My personal library exceeds that. I own and have read her biographies of Lincoln and Napoleon, The History of Standard Oil (unabridged), and (my favorite) her autobiography All in the Day’s Work.

Among her works, until recently, I chose not to read as too dusty even for someone like me is The Tariff in Our Times — a compilation of articles written for The American Magazine and published as a book in 1911. It is an example of the kind of journalism, practiced by Ida Tarbell, Roy Stannard Baker, Lincoln Steffens, and others, which Theodore Roosevelt meant to deride by calling it “muckraking” — but came to be venerated for the elevated way it informed public opinion of that era.

As Finley Peter Dunne’s Mr. Dooley said of her: “Idarem is a lady, but she has the punch.” (The “M,” by the way, stands for Minerva.)

As the years unfolded, and my interest in her writing continued, it seemed more likely to me that I would pick up and read her biography of Judge Elbert Gary (of US steel fame) or of Owen Young (General Electric) than her work on tariffs. That is, until Donald Trump was inaugurated for a second time as President.

I no longer let a political tribe to do my thinking for me, but I still feel a need to make sense of things. Trump, and all that follows in his wake, causes me to be mindful of Kipling’s admonition to keep my head while everyone one else seems to be losing theirs. I compartmentalize the chaos the best I can. I aim to consider the Trumpian dervishes variously as they swirl by and as opportunity permits.

Maybe I shouldn’t have taken up tariffs. But it was the issue most confusing to me. I went to think-tank explainers. I respected their good-faith efforts, but I still felt at sea. IEEPA this. Section 201 that. I couldn’t tell the difference.

So, I thought of Idarem. Thanks to Abebooks, and a republishing company in India, I got a copy of her tariff book.

As I anticipated, Idarem did not take shortcuts. Long sections about wool tariff schedules, I’m sure, made for dry reading and glazed-over eyes 115 years ago — and, of course, all the more so now. But, as I also anticipated, she knew how to leaven her material. Her sketches of “protectionists” like House Speakers Samuel Randall, Democrat of Pennsylvania, or Thomas Reed, Republican of Maine, or of “free traders” in Congress like Roger Q. Mills of Texas or John G. Carlisle of Kentucky, caused me to want to know more about them. They were, at the least, Congressmen who took their roles seriously and would have regarded abject servitude to a President, even of their own party, as preposterous.

She began at the beginning. The first major legislation passed by the First Congress was The Tariff Act of 1789, sponsored by James Madison and signed into law by George Washington. It levied 50 cents per ton on goods imported on foreign ships, 30 cents per ton on goods imported on American-made ships, and 6 cents per ton on goods imported on American-owned ships. It funded the federal government. It paid off federal debt. It protected developing industries.

Over the nation’s first three score and ten years, there was a lot of tariff trial-and-error. The first tariff resulted in an 8 1/2% tax on imports. By the 1828 “Tariff of Abominations,” it was 43%.

The general idea, seldom accomplished to general satisfaction of the nation’s regions, was to place a duty on certain raw and manufactured goods from foreign countries so that, as Idarem explained: “If we find we are getting too large a revenue, we will cut down the duty, if too small we will raise it. In placing these duties, we will do as Alexander Hamilton advised — that is, if there is a young industry in the country trying to produce something which is essential to war or on which on daily living depends, we will protect it from foreign competition until it is established — but no longer.”

In 1857, the national debt was $28,699,831.85. (Yes, back then it was computed to the nearest cent.) The government was taking in more revenue than it expended. The Tariff of 1857 cut duties on imports to an average of 20% — the lowest since 1816. The free list of goods was expanded. Americans, except protectionists of Pennsylvania and New England (where most of the nation’s factories were located), were mostly satisfied with that — at least until a severe economic downturn occurred later that year and government spending was looked for

The economic Panic of 1857 was nothing compared to the Civil War. In 1860 Congress felt hard-pressed to pass budget of $62 million. By 1866, the federal budget was $559 million. By the end of the war, the national debt was a staggering $2,680,647,869.74 (still figured to the cent) — a 93-fold increase within eight years. To finance the war, Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase had to rely on more than high tariffs. Internal taxes on manufactures and consumption, and even an income tax were levied. Federal paper money was introduced.

But the postwar economy proved resilient and strong. By the mid-1880s, industrial workers had trebled from less than 3 million before the war to nearly 9 million. Within the same span, the purchasing power of skilled workers is estimated to have increased by 40%. By 1884, the national debt had been pared to $1,830,528,924. The income tax was the first to go. Internal federal taxes were reduced to those upon alcohol and tobacco. But protectionist tariffs remained — even as the federal government still took in more revenue than it needed.

People from non-manufacturing sections of the country (mostly in the south and west) did not like this. They complained that they were being deprived of the opportunity to purchase less expensive goods from overseas of comparable or better quality than domestically produced counterparts. Wage-earners everywhere had the same complaint.

Idarem described two classes of congressmen: those who study their subjects and those who do not. In the Capital, lobbyists abounded. She wrote in 1911 that, “Ever since 1888, it has been a settled and openly expressed principle in political circles that your protection shall be in proportion to your campaign contribution.”

All this came to seriously concern Grover Cleveland, the reform governor of New York elected the 22nd President of the United States. He was not a free trader as most of his fellow Democrats were. Neither was he a protectionist. He did have a clear notion of what “tariffs for revenue only” should mean. He recognized customs revenue as a tax indirectly paid by the people. When the government was taking in far more than it needed, the people were being taxed unnecessarily.

By the third year of his administration, Cleveland had enough. That year he devoted his entire annual message to Congress on the tariff. He wrote the message himself. Not considered then, nor remembered now, as a compelling wordsmith, Cleveland’s message nonetheless touched the political nerve-endings of the nation. I think it is still worth reading. Here is a sample:

When we consider that the theory of our institutions guarantees to every citizen the full enjoyment of all the fruits of his industry and enterprise, with only such deduction as may be his share toward the careful and economical maintenance of the Government which protects him, it is the plain that the exaction of more than this is indefensible extortion and a culpable betrayal of American fairness and justice. This wrong inflicted upon those who bear the burden of national taxation, like other wrongs, multiplies a brood of evil consequences. The public Treasury, which should only exist as a conduit conveying the people’s tribute to its legitimate objects of expenditure, becomes a hoarding place for money needlessly withdrawn from trade and the people’s use, thus crippling our national energies, suspending our country’s development, preventing investment in productive enterprise, threatening financial disturbance, and inviting schemes of public plunder….

and

Under the present laws more than 4,000 articles are subject to duty. Many of these do not in any way compete with our own manufactures, and many are hardly worth attention as subjects of revenue. A considerable reduction can be made in the aggregate by adding them to the free list. The taxation of luxuries features no hardship; but the necessaries of life used and consumed by all the people, the duty upon which adds to the cost of living in every home, should be greatly cheapened.

The tariff issue did not win re-election for Cleveland. But Benjamin Harrison so fumbled his administration while Cleveland remained the only Democrat capable of winning a national election. Cleveland was returned to the Presidency in 1892. Nonetheless, the high protectionists continued to prevail in Congress.

And Cleveland’s insistence on a gold-based fiscal policy ran counter to his party’s decided preference for a cheaper, more expansive silver-based currency. Cleveland, the only president before Donald Trump elected non-consecutively, became by the end of his second term rejected, even reviled, by his own party. When William Jennings Bryan concluded his famous address at the 1896 Democratic national convention with the peroration “you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold,” Stephen Grover Cleveland was one of the alleged would-be crucifiers.

With Bryan as their standard bearer in three of the next four presidential contests, a Democrat would not be elected to the White House until Woodrow Wilson in 1912. Wilson’s election was in no small measure due to what came to be seen as corrupt Republican intransigence on the issue of protective tariffs.

That perception, especially among the thinking and reading portion of the electorate which in that famous election was critical to its outcome, was itself in no small measure informed by Ida M. Tarbell in the pages of The American Magazine.

She criticized Theodore Roosevelt for, when President, not seeing tariff reform “as a dragon worthy of his steel.” Instead, TR left the dragon-slaying task to his chosen successor William Howard Taft, who ran on a Republican platform which declared for downward recission of tariffs. The tariff issue was such a live wire that early in his administration, President Taft called Congress into special session to resolve it.

“What is a cent to a consumer?” Ida asked in her “Where Every Penny Counts” installment:

“We have 92,000,000 people in the United States. Perhaps there are a few thousand millionaires among us, perhaps a few hundred thousand having an income of ten thousand dollars or more. But in contrast to these there are millions of individuals whose wage is under a thousand. Look over the average yearly wages in our best-paid industries. Take the one which boasts of paying the highest wage — the United States Steel Trust. According to its last report the average wage of its 195,500 employees, including its foremen and clerks and managers, whose salaries in some cases are $10,000 even $25,000 a year, was but $775. In 1905 the average yearly earnings of the men in the cotton industry was but $416. In 1907 the mule spinners in the Massachusetts woolen factories averaged $13.16 a week, the dyers averaged $8.58, the weavers $11.60…. When one comes to examine industries generally, the surprise is not how much, but how little the great body of wage earners receive.”

She opined: “The only chance of peace and of permanency in this country lies in securing for the laboring classes a share of increasing wealth. It is not enough that the wages of men keep up with their forced expenditures — they must go beyond. There must be a growing margin between the two — a margin wide enough for the laborer to see it, and to be able to draw hope and encouragement from it.”

In her final installment, she quoted Rhode Island Senator Nelson Aldrich (grandfather of Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller): “Protective duties are levied for the benefit of giving employment to the industries of Americans, to our people in the United States and not foreigners.”

Then Idarem, in a stemwinder, described what Rhode Island had gained as one of the most tariff-protected states in the union:

“Rhode Island is one of the most perfect object-lessons in the effects of high tariffs in this or any land. An object-lesson should not be overlarge. It should be something you should see, can walk over if you will. Rhode Island satisfies this condition perfectly. In the matter of the protective tariff Rhode Island is the more useful as an object-lesson because she was a well-developed state when the system was applied to her. She had at the beginning of the 19th century flourishing farms…. exporting annually between 2 and 3 millions [of dollars in] agricultural products. She was building many ships, and from her fine ports carrying on a varied and lively trade with other lands. She was well-advanced for the time in manufacturing. Long before the Revolution, Rhode Island’s iron foundries turned out cannon and firearms, anchors and in and all sorts of small wares. When the cotton factory came — and she had the first in the country, the Slater factory of Pawtucket — she was able to make her own cotton machinery. In the manufacture of woolen cloth, she took a prominent place from the start.”

She recognized that, under high-protection, manufacturing in the state had “multiplied and enlarged in a truly magnificent fashion.” To such an extent that “the one thing in the state which stands our above everything else is the factory. It is the factory in which capital is invested and from which dividends are drawn. It is the factory which employs the population.”

“But while she has been making things to sell at this prodigious rate, she has ceased to build ships and send men to sea to trade,,,, Between 1880 and 1900 the improved land decreased by 17 percent.” The state could no longer satisfy many of her own agriculture needs. “She buys her apples on the Pacific Coast, her flour from the Mississippi Valley, and her meat from the Beef trust.”

Regarding Senator Aldrich’s claim: “The first feature of the textile industry in Rhode Island which strikes even a casual observer is that the operatives are not American; they are distinctively foreign — new-come foreigners. Less than 16% of them, as a matter of fact, are born of what the industrial authority of the state calls ‘United States fathers,’ the other 85% are in percentages in order of their naming here: French Canadians, Irish, English, Italian, Germans, Scotch, Portuguese, Poles, and Russians, besides a considerable number classed under ‘other countries.’”

“A second surprise awaits the student of these Rhode Island laborers blessed by protection. They are an unstable quantity. They must be constantly replaced. The ‘benefits’ do not hold them.” And "in one of the first settled states of the Union, one of the most advantageously situated, one offering the best opportunities for diversified occupations, one of the richest in its per capita product and bank deposits, only a fourth of the population live in houses which they own.”

She described the oppressive heat, poor ventilation, and appalling sanitation of many Rhode Island factories. Her book makes no mention of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire which occurred on March 25, 1911, in Greenwich Village, New York City.

Despite President Taft’s desire to keep his party’s pledge to reduce tariffs, the Payne-Aldrich Tariff of 1909 — the result of the special session called by the president — was not seen that way. Taft signed the bill into law in the hope, even expectation, that the new tariff regime would stimulate the economy and lead to his re-election. Instead, with the catalyst known as TR, the tariff split his party and led to the election of Woodrow Wilson in 1912.

Tariff revulsion had reached such a pitch that the nation was willing to supplant the tariff with a federal income tax — even if it took a constitutional amendment to do so. Which it did. The 16th Amendment, offered by Congress during its tumultuous tariff summer of 1909, was successfully ratified by 36 of the 48 states by February 1913.

The Tariff in Our Times

With an income tax, tariffs receded front the front burners. That is, until the stock market crash of 1929. The Tariff Act of 1930 (“Smoot-Hawley”) was the congressional response (Republican Congress with President Hoover) intended to protect domestic industry and agriculture from European competition. But it was answered by retaliatory tariffs from abroad, and Smoot-Hawley is regarded as having exacerbated a severe depression into the Great Depression.

By Smoot-Hawley, Congress used its constitutional prerogative to set the highest tariff schedule since the Civil War. But the Tariff Act of 1930 also contains a section, 338, still in effect though it has never been used, which delegates to the President the power to impose an ad valorem tariff of up to 50% of the value of goods imported from any country deemed by the President to have been discriminating against our nation’s commerce

In 1934, Franklin Roosevelt’s Democratic Congress passed the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act. By the RTAA, Congress delegated to the President the authority to negotiate with trading partners and to raise or lower the Smoot-Hawley tariff levels. The Roosevelt administration used this delegation of congressional power to reverse tariff protectionism. In 1934, the tariff amounted to 46%. The RTAA was renewed by Congress several times, thus enabling the executive branch to continue the lowering of tariffs.

By the time of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, the tariff was 12%). This law delegated more congressional tariff power to the to the president, empowering the executive to change tariffs, up or down, as much as 50% as well as to eliminate entirely tariffs already at 5% or less. This legislation also empowered the president to impose non-tariff trade barriers. And its Section 232, written in the height of the Cold War and still in effect today, authorizes the president, to initiate a tariff on a specific product if importation of that product “threatens to impair national security.”

The Trade Act of 1974 delegated more congressional tariff responsibility to the president — and the term “fast-track” became associated with presidential tariff authority. Its Section 201, still in effect, authorizes the president to impose tariffs to protect threatened domestic industries. Its Section 301 also remains to invest the executive branch’s United States Trade Representative with broad authority to investigate unfair trade policies that harm our nation’s competitiveness in the world market and to take retaliative tariff action accordingly. Tariffs implemented under 201 or 301 are, however, subject to a time frame of consulting with and reporting to Congress.

The International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA) was an update of the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917. It delegates to the President congressional authority to regulate imports in the context of a declared national emergency. It is this law which President Trump has been thus far invoking to justify his sweeping tariff regime. But Congress has not yet joined in any of the President’s proclaimed national emergencies. Moreover, IEEPA empowers the president to regulate imports. The word “tariff”, significantly, is not to be found in the text of IEEPA.

In the aftermath of World War II, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade was signed by 23 nations, including ours. GATT instituted a rule-based system for resolving international trade disputes. As GATT increased in influence, the perceived need for unilateral tariffs receded. GATT grew to include 128 nations before, in 1995, it morphed into the World Trade Organization. The WTO currently has 164 member nations and monitors 98% of world trade.

The North American Free Trade Agreement of 1994 between the United States, Canada, and Mexico was an extension of the 1988 Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement. NAFTA, in turn, was replaced by the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) negotiated during the first Trump administration.

With the advent of the World Trade Organization and with North American trade agreements, Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 and Sections 201 and 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, though extant, had come to lay almost dormant as instruments of trade policy. That is, until the first Trump administration when “play in the joints” in the language of these statutes was applied in ways they had not been applied before — beyond, arguably anyway, Congress’s original intent.

While Section 232 empowers the President to impose tariffs for reasons of national security, the language of the statute is vague in its definition of what is actually a national security threat. Making use of that ambiguity, Robert Lighthizer, the U.S. Trade Representative during the first Trump administration, launched investigations into the importation of steel, aluminum. automobiles and automobile parts, uranium ore and uranium product, titanium sponge, mobile cranes, and vanadium.

(I am very inclined, given that my station in life is largely due to the making of steel, to view the domestic production of steel as a national security concern. But I also feel constrained to acknowledge that our county remains the third largest producer of raw steel in the world. And only 3% of our domestic steel production is consumed by our military.)

In contrast to recent Trade Representatives, Lighthizer was more likely to work outside the WTO. Six times, bypassing the WTO, he used Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 in trade disputes.

President Biden, of course, was quick to reverse many of President Trump’s policies. But the Biden administration kept Trump’s Section 232 tariffs in place. The Biden administration also expanded the Section 301 tariffs against China.

Donald Trump in 2024. whether people took him seriously or not, was open in his advocacy for more tariffs. But, here in mid-summer 2025, it remains unclear whether his main purpose in tariffs is to raise revenue, or to balance foreign trade accounts, or as an instrument to be used to address national emergencies. The emphasis seems to vary by the news cycle.

(Which of his emergencies — border, drugs, trade — have we not known about a long time? I don’t deny these issues reaching, may have already attained, a critical mass of importance. But an “emergency” implies something “sudden.” These issues have been long festering. Trump is among our “leaders” who, for their own machinations, have been content to let them fester.)

President Trump’s second administration was hardly two weeks old before he announced, claiming IEEPA authority to respond national emergencies on immigration and drug trafficking, 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico and 60% on China. He promised a 10 to 20% universal tariff on all U.S. imports, asserting that nearly all nations are economically exploiting us.

The tariffs upon Canada, Mexico and China have gone up and down in a confusing welter — but usually a few weeks (now sometime in August) away from a threatened new height.

On April 2, “Liberation Day,” President Trump personally announced sweeping tariffs on all nations in direct relation to the imbalance of trade existing between those nations and the United States. The Rose Garden presentation was not without its absurdities. Among the charts, it was recognized that Lesotho, a land-locked nation in southern Africa, was getting punished with a 50% tariff on goods shipped to us because there is that great a disparity between what Lesotho sells to us versus what they buy from us. Lesotho is a poor country. It sells textile products and raw materials overseas. Its per capita income is less than $1000 a year. Lesotho would probably buy more from us if they could afford it. Lesotho is hardly exploiting us.

The stock market, and the bond market (the rate at which investors are willing to purchase federal debt), did not take well to Liberation Day. The administration quickly backed down from immediate implementation of these draconian tariffs — instead imposing a 10% universal tariff with a 90-day timeline for the nations of the world to negotiate individual trade agreements with us. That timeline was set to expire on July 9. It has been extended to August 1.

The stock and bond markets recovered. Conventional wisdom says markets crave stability. It seems the prevailing market assumption is that, when all this shakes out, it will result in no more than a 10% tariff on goods entering the United States — and the American and world economies, on the macro, can absorb that. The markets seem to have talked themselves into a hopeful sense of stability.

Whether President Trump will be content to let it shake out in this 10 % -solution way remains to be seen.

But, on the micro, not every business can absorb a 10% increase. Maybe Wal-Mart or Home Depot. But not V.O.S. Selections, an importer of hand-made wines, located in New York City. Or FishUSA, a seller of imported fishing tackle, located in Fairview, Pennsylvania. These companies are among several small businesses which, represented by the Liberty Justice Center, brought a lawsuit to the United States Court of International Trade to dispute the administration’s legal authority to implement tariffs under IEEPA. They were joined, in an accompanying suit, by attorneys-general from twelve states making the same challenge.

On May 28, the USCIT, in a unanimous 49-page decision, found in favor of the plaintiffs. The Court emphasized that they were not weighing in on the wisdom of the President’s tariff policy. Instead, they were ruling on the constitutionality of his action. The court wrote: “The Constitution assigns Congress the exclusive powers to ‘lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises’ and to ‘regulate Commerce with foreign Nations’…. The question in the two cases before the court is whether the International Emergency Powers Act of 1977 delegates these powers in the form of authority to impose unlimited tariffs on goods from nearly every country in the world. The court does not read IEEPA to confer such unbounded authority and sets aside the challenged tariff imposed thereunder.”

The Trump administration immediately appealed to next level circuit court. That court stayed the USCIT decision pending the outcome of the appeal — thereby letting the 10% tariffs meanwhile remain in place. The appeal is scheduled to be heard on July 31 — the day before the administration’s arbitrary date of August 1 for the nations of the world to come to terms.

The case appears likely to go to the Supreme Court. If you were small business dependent on exports from overseas, who would you want to win? If you were a foreign nation, what would you do? We have an idea of what Japan would do.

The White House recently announced, “a historic trade and investment agreement with Japan.” The details of the agreement have not been made public. Reportedly, the Trump administration promised not to levy a threatened 25% tariff against Japan and instead pledged a tariff of no more than 15%.

I maybe a smalltown hick, but I’m going to ask about the emperor’s clothes. By what authority could he make such a general tariff pledge to Japan? Is he counting on winning the IEEPA appeal? Or is he using, for the first time ever by a president, Section 338 from Smoot Hawley? If so, why is Section 338 of Smoot-Hawley a good idea now after laying in its box untouched for 90 years?

There are those who would argue that Section 338 is from its inception an unconstitutional delegation by Congress of its own responsibility to the Executive. I think there may be a majority on the Supreme Court who, if asked, would agree.

The USCIT opinion under appeal cited a famous Supreme Court concurrence by Justice Robert Jackson in Youngstown Sheet and Tube v. Sawyer where the Supreme Court found against the government when it tried to take over a steel industry during the exigencies of the Korean War. Jackson, who had served as both Solicitor General and Attorney General for FDR, observed, from personal experience, that presidential power falls into three general categories. “Presidential powers are not fixed but fluctuate, depending upon their disjunction or conjunction with those of Congress,” he wrote. They are at their highest when “the President acts pursuant to an express or implied authorization … for it includes all that he possesses in his own right plus all that Congress can delegate.”

The middle level: "When the President acts in absence of either a congressional grant or denial of authority, he can only rely upon his own independent powers, but there is a zone of twilight in which he and Congress many have concurrent authority, or in which its distribution is uncertain. Therefore, congressional inertia, indifference or quiescence may sometimes, at least as a practical matter, enable, if not invite, measures on independent presidential responsibility. In this area, any actual test of power is likely to depend on the imperatives of events and contemporary imponderables rather than abstract theories of law.”

The lowest level: “When the President takes measures incompatible with the expressed or implied will of Congress, his power is at its ebb, for then he can rely only upon his own constitutional powers minus any constitutional powers of Congress over the matter.”

It seems to this observer that, in regard to the IEEPA tariffs, President Trump doesn’t have much of a constitutional leg to stand on. Thus, in the Robert Jackson explication of presidential authority, the IEEPA tariffs are in the lowest tier. Except for one thing:

The docile Republican majorities in Congress don’t care. "L’etat, cést moi,” is Donald Trump’s governing philosophy — and the Republicans in Congress are passively going along for the ride.

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 and Sections 201 and 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 may be unconstitutional delegations of congressional authority too, but they do have several decades of accepted jurisprudence behind them. However, they are statutorily piecemeal and require the kind of sustained heavy lifting in cooperation with Congress that the Trump administration does not want to engage in — if they don’t have to.

If Congress doesn’t care, why should the federal courts?

Well, because the plaintiffs in the V.O.S Selections v. United States of America have been not only accorded standing, but their lawyers have also argued persuasively. In our federal judicial system, David can still take on Goliath. And in our federal judicial system, reason and fairness still have a pretty good chance of prevailing.

Trump’s tariffs may well be good policy. But, in our constitutional framework, tariffs are to be implemented by Congress, not the President. Our founders anticipated a Congress that would be jealous of its powers, not a Congress that would shirk them. Not did our founders anticipate an electorate acquiescent with such a quiescent Congress.

If Trump’s tariffs stand, they will be a tax. As such they will have the same effect as tariffs did in Idarem’s day. They will be more burdensome to low-income persons and families than to high income. Even if they do not rise above 10%, that 10% will be absorbed by the affluent with little or no difficulty. More than 70% of our nation’s wealth is held by one tenth of our households. Less than 3% of our nation’s wealth is owned by five tenths of our households. (Those statistics come from no less a source than the Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis.)

What was it that Idarem wrote?

“The only chance of peace and of permanency in this country lies in securing for the laboring classes an increasing share of increasing wealth. It is not enough that the wages of men keep up with their forced expenditures — they must go beyond. There must be a growing margin between the two — a margin wide enough for the laborer to see it, and to be able to draw hope and encouragement from it.”

Sources:

Ida M. Tarbell, The Tariff in Our Times, New York, 1911.

Alyn Brodsky, Grover Cleveland, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2000.

Doris Kearns Goodwin, The Bully Pulpit, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1913.

Henry Steele Commager, editor, Documents of American History, New York, 1948.

Adam Looney and Elena Patel, “Why Does the Executive Branch Have So Much Power Over Tariffs,” Brookings Institute, January 15, 2025.

Jennifer Hillman, “Trump’s Use of Emergency Powers to Impose Tariffs Is an Abuse of Power,” Center on Inclusive Trade and Development, February 2025.

Inu Manak and Helena Kopans-Johnson, “Tariffs on Trading Partners: Can the President Actually Do That?” Council on Foreign Relations, February 2025.

U.S. Court of International Trade, Opinion, V.O.S Selections v. U.S.A., May 28, 2025.

U.S. Supreme Court, Justice Jackson Concurrence, Youngstown Tube v. Sawyer, 1951.

Steven Calabresi, "President Trump’s Reduced Tariff/Taxes Are Still Unconstitutional,” The Volokh Conspiracy, 10 April 2025.

White House Fact Sheet: “President Donald J. Trump Imposes Tariffs on Imports from Canada, Mexico and China,” February 2, 2025.

White House Fact Sheet: “President Donald J. Trump Declares National Emergency to Increase our Competitive Edge, Protect our Sovereignty, and Strengthen our National and Economic Security,” April 2, 2025.

White House Presidential Actions: “Defending American Companies and Innovators from Overseas Extortion and Unfair Fines and Penalties.” February 21, 2025.

White House Fact Sheet: “President Donald J. Trump Secures Unprecedented U.S. - Japan Strategic Trade and Investment Agreement.” July 23, 2025.

Scott Lincicome, “Trump’s Trade Fight Is Just Getting Warmed Up,” The Dispatch, June 5, 2025.

Holland & Knight, “Reciprocal Tariff Update: State of Bilateral Negotiations,” July 22, 2025.

Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis, “Levels of Wealth by Wealth Percentile Groups,” 1st Quarter 2025.

Congressional Research Office, “Congressional and Presidential Authority to Impose Import Tariffs,” April 23, 2025.

Hey Woody! Excellent article. Very informative with great historical background. We need to get together soon. Hope your summer is going well. Doc